Light Art

The immaterial medium of light has long found its way into artistic production. As a symbol of the divine, it left its traces in the church windows and gold grounds of the Middle Ages; in its profane manifestation, it is first found as a means of modelling landscape in the pictures of the Early Renaissance, and, in the Baroque period, is put to the service of the dramatisation and mise-en-scène of painting, sculpture and architecture. When the technological revolution began, light became the bearer of modern belief in progress and the leitmotiv of Futurism. It departed from the canvas via theatre, photography and film, in order to become, itself, an object of contemplation.

‘I form the light’ – a dance as the beginning of an art direction

She became the star of art nouveau and symbolism. She became the central ornament of the nascent Jugendstil. Edison and the Lumière brothers captured her dance, Toulouse-Lautrec created a whole series of lithographs after her image, and numerous designers used motifs from her dances for lamp bases and glass windows. She was Loïe Fuller. All that settled like layers of patina on a personality who debuted in Paris’s Folies Bergère in 1892, with a dance that celebrated light not only as an aesthetic event but, simultaneously, as an unprecedented lender of form to the synaesthesia of light and movement, light and space. Wrapped in an oversized white cloak of crêpe de Chine, fabric which concealed the aluminium rods that extended her arms’ radius, and shone upon by arc lamps recessed in the stage floor, she brought to the audience in the otherwise fully darkened stage space a scenography of flowing and whirling panels of fabric, a transforming construct of light. ‘Je sculpte de la lumière’ – ‘I form the light’ is the dancer’s programmatic caption for her creations. A postulate that shines through to this day in every artwork created using light.

Light the liberator

Yet it was the emerging resource of photography, getting light noticed as a medium for the first time, that liberated objects from their materiality as it transformed them into pictures. Lázló Moholy-Nagy summarised this experience in 1928 as follows: ‘The light-sensitive layer – plate or paper – is a tabula rasa, a blank page on which one may make notes with light, just as the painter... uses his tools.’ In saying that, the native Hungarian and, from 1923, artist at the Bauhaus in Dessau was thinking less of photography as a medium than, rather, of a ‘New Vision’. The motivating element was the demand for objectivity, for an art free of the fluctuating moods and sentimental feelings imputed to bourgeois art: a technical art, a mechanical art in pace with the times and, accordingly, with the early 20th century’s social upheavals.

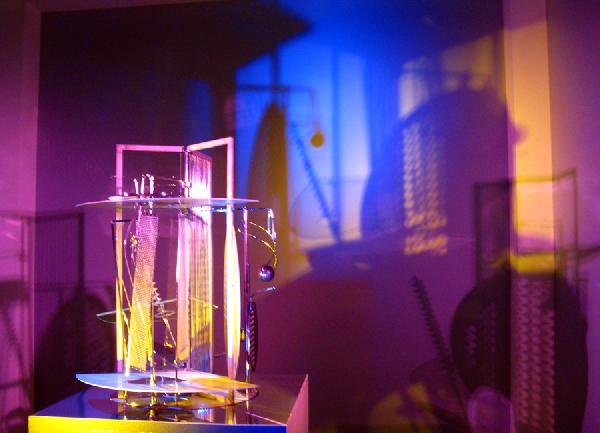

Thus one of the best-known executions of this attempt is represented by the light/space modulator, developed by Moholy-Nagy from 1920 but not put on display until at the Deutscher Werkbund exhibition in Paris in 1930. This ‘light prop’ consists of a cube-shaped box with a circular opening (stage opening) on its front face. Around the opening, on the reverse of the front face, a number of yellow, green, blue, red and white-coloured electric light bulbs are mounted. Inside the box, parallel to the front face, there is a second plate with a round opening that likewise features different-coloured electric light bulbs. Individual light bulbs light up at different points according to a pre-defined schedule. They illuminate a constantly moving mechanism structured out of partly transparent, partly openwork materials, in order to achieve shadows and colour projections that are as linear as can be on the walls of a darkened space.

Light, and no redemption

However, the political changes in Germany had an immediate destructive impact on Moholy-Nagy’s experiments and hence on the visions and utopias of the artistic avant-garde. For, just a few years later, the cultic dimension of light which also appears with Moholy-Nagy was misused as a political instrument. With the use of flak spotlights for the Nazis’ propaganda marches in Nuremberg, Berlin and other German cities, Albert Speer not only proved his penchant for the dramatic, but, simultaneously, understood himself to be the high priest of the calculated use of light and its emphatic effect on the masses. By 1939, the spotlights’ monumental shining had perverted one of humanity’s oldest notions into its opposite. It twisted the notion that light brings redemption.

In the subsequent period, therefore, artistic/technical experiments were no longer possible and, just a few years later, ‘natural’ light also lost its innocence in the end, with the atomic flash and the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

The radical concretisation of light

With that, the second half of the 20th century saw the radical concretisation of light. With the corollary that natural light alone is no longer a potential theme of art, the modern era saw a second beginning, in the process discovering – at first in clear association with Moholy-Nagy’s Bauhaus experiments – artificial light as its artistic material again.

In Paris, the artist Nicolas Schöffer, he too, like Moholy-Nagy, a Hungarian, he too a utopian of a total urban aestheticisation, had been already developing spatial-dynamic light architectures since 1948. The objective of his activity: a cybernetic city. A city that reacts to times of day, temperatures and weather with light and movement. This largely uninterrupted, future-oriented and technologically euphoric dimension also defined the works of the Düsseldorf artists’ group ZERO, to which, among others, Heinz Mack, Otto Piene and Günther Uecker belonged.

Using hand-held lamps at first and then, increasingly, mechanical, electrically programmed structures, Piene, the most efficient organiser and the enthusiastic theoretician of the group, developed veritable light ballets and plays of light.

Dan Flavin – a fluorescent tube becomes an icon

At the same time, the tendency to concentrate on ‘pure’ light and its effusion in the room was to be found in the works of American artists. 1963 saw the creation of that first icon on which the American Dan Flavin bases his entire oeuvre to this day: The diagonal of May 25, 1963 to Constantin Brancusi, an industrially produced, yellow light-emitting fluorescent tube, which was secured to the wall of a room at an angle of 45 degrees to the horizontal.

Unlike traditional plastic arts and sculpture, which are modelled using light from outside, in Flavin’s work, light penetrates, conversely, from inside to out. The light’s object is not a body, but the space in which it is effused.

Light spaces

Sensoriality that shines out intellectually subsequently characterises the oeuvre of another American artist: James Turrell. Turrell presents light in its physical facticity, in its metaphysical effect. He is an artist whose work is focused entirely on creating an intellectual experiential quality of spaces dissolved by light. Intangible light spaces, seeming dimensionless and boundless – spaces of pure sensory experiences that are always open to transcendental interpretations as well.

James Turrell’s light installations share with the works of Dan Flavin, but also of Robert Irwin or Douglas Wheeler from the period ca. 1970, their self-reference, the investigation of light as material with its physical/optical properties and its spatio-temporal effect on the beholder.

Iconography of consciousness

However, at almost the same time, a second tradition of dealing with light as artistic medium emerged alongside abstract light art. It has its roots in illuminated advertising. Whereas, in 1879, it was the development of the commercial light bulb that covered cities with luminescent advertising in its wake, that was superseded from 1912 by the neon advertising symbol, the ‘living flame’, the name in America for the neon tube, which was now being used on a mass scale in order to recreate symbolic advertising emblems or lettering.

While this fashion suffered a nosedive in the early 70s of the twentieth century, within their very different artistic concepts artists were discovering in the thin, malleable glass tube filled with different gases the ideal starting material for creating light constructs out of individual words, phrases or whole pictures.

Protagonists of the symbolic include François Morellet, Keith Sonnier and Maurizio Nannucci, while the fluorescent tube is put to less abstract use by Joseph Kosuth, Mario Merz and Bruce Nauman.

Light and shadow

Simultaneously, art criticism at that period was preoccupied by the notion that the powerful fascination exuded by colourful lights could be a hazard for artistic work. So it was pointed out, again and again, that these materials could be successfully integral to the artistic process only as long as the material’s fascination did not force aesthetic discourse into the background, as long as the fluorescing body of colour was legitimised by a convincing artistic concept and did not disintegrate into a decorative end in itself. At that point, therefore, art critics’ focus was very soon directed towards artists whose works foregrounded substantial messages.

Christian Boltanski, for example, the artist who, via the concept of securing evidence shaped by critic Günther Metken at that period, advanced to become the most paradigmatic producer of trails. On the heels of showcases containing childhood documents came the so-called ‘Archives of Remembrance’, for which Boltanski used the same elements again and again from 1969: tin boxes (biscuit tins), photos and archive lamps and, on them, works featuring simple wire figures which, illuminated, get up to their demonic mischief as shadow-pictures on gallery and museum walls. Light/shadow constructs. Nightmares of our own interiority.

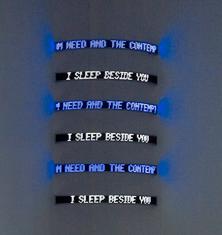

Meanwhile, in America, artist Jenny Holzer was getting herself talked about. Her luminescent writing work began to confuse unwitting beholders and passers-by in built and public space alike. She had these messages, known henceforth as Truisms, run on the electronic billboard on New York Times Square for the first time in 1982, amid all the hustle and bustle where advertisements, news and events information are jumbled together; and defined a socially engaged, politically oriented art.

The illusoriness of the projective promise

In the 1980s, Jenny Holzer’s illuminated text was joined by light projection. Artists inspired by the light-emitting apparatuses included Andreas M. Kaufmann, Michel Verjux and Mischa Kuball. The works by Andreas M. Kaufmann, with his iconographically charged, always venue-specific, slide projections, are countered with the power of modern abstraction by Michel Verjux: the central theme of the latter’s work is the discrepancy between the shine of the projection and the projection surface shone upon, which usually only appears in fragments. Düsseldorf artist Mischa Kuball also, like Kaufmann, uses projectors for his artistic interventions, which mostly encroach on the public space. He most often uses gyroscopic projectors, which allow him to modify light emission or motif incessantly.

Art and science

A new connection between the disciplines of art and science, which had been kept distinct since Cartesian times, became discernible precisely in the area where artists were operating with light as their material. At their points of intersection, artists developed pictorial analogies and metaphors which are not cited as reference values, but re-encounter one another in an overall structure that can be experienced aesthetically. In 2009, at the Venice Biennale, the American artist Spencer Finch presented a true to scale, three-dimensional model of the moon’s atomic structure. Finch used different-sized lightbulbs and fixtures connected by metal rods in order to recreate the molecular components of the moon dust collected by the astronauts of the Apollo 17 mission in 1972 and subsequently analysed for its chemical components. As a reply to the scientific enlightenment’s dissolution of mythical imaginings that had defined moon’s image and its influence on life for millennia, Spencer Finch offered a new work that is experienced visually and sensorially.

BIT.FALL (2002 – 2006), by Julius Popp, is also a work situated between technology, science and art. The basis of this work is the artist’s investigation concerning the speed at which information is gathered, exchanged and updated in modern society. The information represented by words in BIT.FALL is supplied by software operating on a statistical algorithm. Within a period defined by the artist, this software filters news from the internet and transfers these values to the BIT.FALL controls. In fractions of seconds, these controls occasion the fall of hundreds of drops at certain intervals, thus giving rise to a ‘waterfall’ of words. Each drop of water becomes a liquid, fleeting ‘pixel’ or ‘bit’, the smallest component of this information.

Jan-Peter E.R. Sonntag, obsessed with waves and total monochrome, is also among those artists who step over the boundary line to science. Together with the company NARVA, in 2009 he designed a plasma that oscillated greenly, and with unprecedented intensity, contained in a likewise specially manufactured glass body and presented in the form of a three-legged standard lamp.

Beaming across boundaries

As the 21st century began, boundaries became blurred. It was no longer possible to talk about light art as the sole province of artists who make light itself the object of contemplation. Light art was no longer a conceptualisation founded on any clear attribution but, rather, a thematically open area in which light found its way into artistic practice as an immaterial resource. In this context, light becomes a component of complex questions in relation to past and present-day, societal and individual processes and phenomena. It finds a use in the examination of cultural differences (Anny & Sibel Öztürk, Haegue Yang), of political, media and economic co-optation (Via Lewandowski) or of both private and societal culture of commemoration. And it loses its clear attribution and fixed definition in the works of those artists who, besides entirely personal work and life circumstances, do not exclude architecture, design history and day-to-day culture references (Tobias Rehberger, Olafur Eliasson).

Light art and the parameters imposed on it

Naturally, all works that use luminescent objects, or that even declare light as the object of contemplation itself, can be described as light art, but it is worth drawing a boundary to illumination. This delimitation ensues on the model of a concept of art which feeds on bodies of work, on a subject-based, at once temporal, geographical, social and political perspective taken on by artists – under the use of the medium of light. To go into general terms again, light art therefore means art that makes use of light’s technical possibilities in order to expand its own experiential force, that creates spaces and places for remembrance, history, for resistance, poetry and dreams and understands itself as a conceptual and empirical space in which the artist assumes a reflexive attitude.

Matthias Wagner K